The Eagle

Released: 2011

Starring: Channing Tatum, Jamie Bell

Period of history in focus: Roman Britain (specifically 140 AD)

I remember seeing the preview for The Eagle for the first time and giggling to myself. Another terrible Roman epic was on the horizon. Then, I promptly forgot the film and went about my business. To my surprise, the film received decent reviews when it was released. It wasn’t terrible? This began generating my interest and for the past several months I’ve been interested in watching the film. This might ruin my credibility, but: I didn’t hate it. Yes, the acting is not great, and there are points of the plot the don’t work very well, but overall The Eagle has a solid premise and it’s executed fairly well. This isn’t to say that it’s also historically accurate, because it’s not. I’m willing to cut it some slack because it is based off a novel, but you know how I am about letting movies saddle people with inaccurate impressions.

Most people probably don’t know much about the Roman occupation of Britain. Maybe you’ve heard of Julius Caesar and his conquests there. This was in the 50s BC. He didn’t actually accomplish that much, and certainly didn’t conquer the island. Part of this had to do with the fact that when a Roman fleet of ships sailed across to the island, a storm whipped up before they were able to land and took most of the ships out. Both sides saw this as an omen – although the Romans took it as a negative one and the Britons saw it in a more positive light – and the Romans more or less left Britain alone for awhile. Other reasons they weren’t terribly involved: Britain is far away from Rome, Italy, the center of the empire; the Romans had to deal with rebellions in Gaul, which was closer to home; did I mention Britain is far away? This didn’t dishearten the Romans completely, as they are a people who really enjoy their conquests, and sneaking into the 40s AD, they returned to make their conquest happen.

The main rebellions happened in the 60s AD, including the one you might have heard about: Boudica’s rebellion. Following these rebellions, the Britons started to realize that they couldn’t win against Rome. As ever, the Roman army was a well oiled machine and the British tribes that were trying to fight them off simply couldn’t unify or make a cooperative effort. Rulers of various tribes at this time started to see the benefits of allying with the Romans, including increased social status and the agreement that the army wouldn’t kill their people and burn their villages.

I told you to give them fealty and agree to honor their gods, but YOU said we should maintain our independence.

The tribes in the north of Britain (or Scotland, if you prefer) always gave the Romans headaches and they never quite managed to establish themselves there. But by the 100s AD and following, most of the big rebellions were quashed and soldiers largely had nothing to do. That’s where we can begin to address the premise of this film.

There were three or four legions in Britain, keeping a hold on things. One of these was the Hispania IX, or, Ninth Spanish legion (called the Ninth Roman legion in the film). For awhile it was believed that this legion of men disappeared somewhere in northern Britain under mysterious circumstances – as if a legion of soldiers could disappear under mundane circumstances. The reason for this is that records show the Ninth Spanish legion as being in Britain, taking up the fort at York. They left York at around 108 AD, and a new legion moved in around 122 AD. There aren’t really anymore records of them. So what happened?

Both the anthologies that I read claim the idea that they somehow disappeared in Britain is not credible. Perhaps they were disbanded and the men sent to other legions. Perhaps they were sent away from Britain. There are records from later years which might refer back to the Ninth Spanish Legion somewhere in the Netherlands. It’s not really certain, but the big exciting mystery seems to be a fabrication.

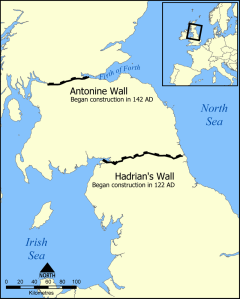

Whatever the case, the disappearance or disbanding of this legion certainly did not serve as the catalyst for Hadrian’s Wall, as the film claims. The opening narrative to the film informs the audience that the humiliating defeat of the Ninth Roman Legion caused Hadrian to build a wall so Rome could never face another embarrassing defeat, by separating the Romans from the barbarians.

The official story was that the wall would act as a barrier. But, considering how far North the wall was, there were many thousands of native Britons living among Roman soldiers, building towns around their forts and in some cases making families with the Romans. This, in effect, makes the wall kind of useless for separation purposes. The more practical reasons for the construction of the wall have to do with boredom and travel. As most of the major rebellions had already been over and done with for awhile by 122 AD, many of the soldiers didn’t have much to do. Some of the forts had begun to slack in their duty, and when Hadrian visited Britain he noticed that parts of the army had gone sloppy. Ordering a wall would serve as metaphorical border, but would also give soldiers something to do, and a reason to start whipping them into shape again. The wall was intended to cross the width of the island, and with the forts and towers in the wall close to roads, it seems that the true purpose was to regulate traffic and movement north and south.

For these reasons the wall wouldn’t seriously be considered the end of the world. Particularly because there were forts and roads occupied by Romans north of the wall. Not to mention that Antoninus Pius built another wall twenty years later, even farther north.

Now, this movie begins in 140 AD, which is two years before construction on the Antonine Wall began. So I’ll cut it some slack for making business about Hadrian’s Wall being cooler. However, we have Marcus Flavius Aquila (played by Channing Tatum and his abs) being transferred to Britain as a cohort commander somewhere in Roman occupied southern Britain. Within his first several days he has to deal with the grain delivery being delayed, an assault on the wall, and then the patrol he sends out for the grain being kidnapped by yet another tribe and whipped by some over the top Druid. This is exciting, but a little nonsensical. If this is truly south of the wall, then this sort of thing seems unlikely. Furthermore, I don’t know why this Druid is wandering alone.

First, from the limited amount I know about Druids, it seemed they banded together. Secondly, back in the 60s AD when all the big rebellions were going on, Roman leaders noticed that the Druids were a threat. They acted as enforcers of law as well as a potential focal points for the tribes around them. Most dangerously, the Druids were literate. The Romans moved in and destroyed their stronghold in Anglesey, which effectively helped them gain more control over various tribes. Overall, I found the beginning of the film to be entertaining, but not very believable on a historical level.

The battle that follows just outside the fort looks like what you might expect by now from a film that involves the Roman army. They march out together, and use their shields to create the turtle formation. The difference here is that Marcus gets injured and is sent away, never to see the real fighting force of the Roman army for the rest of the film. What the audience doesn’t get to see is history.

That’s okay. I don’t have a problem with a film dipping into fantasy. So long as you realize that Marcus and his slave, Esca, traveling north to retrieve that lost Eagle of the Ninth is mostly absurd.

From here on out, I have a few small issues I’d like to address.

North of the wall

The scenery in this movie is beautiful. Most of northern Scotland would be gorgeous highlands and largely unoccupied areas. However, as I already mentioned, Hadrian’s wall did not mark the end of Roman occupation. Marcus and Esca would have passed some forts and settlements by Romans north of the wall, and probably would have encountered some roads too. The soldiers at the wall would never have said something stupid like, “Don’t you know this is the end of the world?” This really irked me.

The Eagle (or the standard)

This is actually a thing. For anybody who has seen the television series Rome, you might remember a similar plot about retrieving the lost standard. This was extremely important and a symbol of Roman honor, and the film actually hinges around an idea Romans would fight for.

Esca, I know you despise Rome and the Eagle represents Rome, but you'll still help me get it back, right?

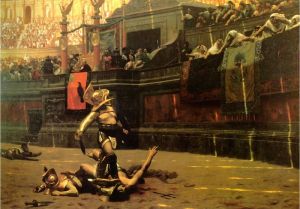

Esca

I like the introduction and treatment of Esca throughout the film. He is treated with proper disdain by most of the Romans around him. For anybody who didn’t read my posts on Gladiator, slaves were reviled by the Romans. As people who were forced to do labor and accept physical and verbal punishment, they were considered as lowly as someone could be. I like the idea that Marcus grows to respect him. What I would have liked more, was to see Marcus be more biased against him from the start. He shouldn’t trust him, and should treat him worse to begin with to make their transformation into best bros more profound.

Another thing I struggled with was Esca’s role north of the wall. I can believe that enough tribes speak a similar enough language to allow them to communicate, but we already know that the tribes warred each other as much as Rome. Why do they all accept him? Why doesn’t somebody try to kidnap him? I found it dubious that the fierce tribe in the north accepts him as an honored guest.

The size of the legion

An entire legion all told would have about 5,000 men. What confused me was that Marcus said his father was in charge of the first cohort of the Ninth legion. A cohort would be considerably smaller than a legion. At the most basic organizational level of the army you had centuries. Each century typically had about 80 men. A cohort would be made up of six centuries, for a told of about 480 men. The beginning of the film tells us that all 5,000 men of the Ninth legion disappeared, and everybody blames Marcus’ father. But, in charge of a cohort, he would only have been responsible for 480 of those men, and therefore wouldn’t be the center of disgrace. The numbers don’t really add up.

The survivors

Marcus and Esca run into a man from the destroyed legion who saved his own life by fleeing the scene. He explains what happens by saying that four tribes converged on them and owned them heartily. Why did these four tribes ban together? Why do we only get to meet one of the tribes? Also, why are they such huge dicks?

As for the survivors, they have all made lives and families with various northern tribes. The guy we meet, Lucius Cauis Metellus, or Guern, even delivers a diatribe about how Roman expansionist policy is bad. If these men now have families in the north and have grown to see what sucks about Rome, why do they fight to protect the standard at the end of the film? Perhaps their Roman values are too deeply ingrained in them, or maybe they were moved by Esca’s plea to help save his best bro, but what kind of honor do they have to preserve if they have been operating off an entirely different system of honor for the past twenty years?

You're saying I can die for an empire I no longer believe in, or stay at home and live with my family? Hmmm...that's a tough one.

The lack of women

I think the only women in the film are the several we see in the village way up north. One of the tribesmen attacks Marcus for looking at his sister. At this point I realized that we hadn’t heard a woman speak the entire movie, and we didn’t get to from that point forward. I understand the argument that a war focused movie might not have women, but there’s a chunk of time spent at Marcus’ uncle’s villa. Maybe the senator we meet could have brought his daughter and her spout ignorant crap instead of whoever that guy was. Then at least we’d get to hear a woman talk.

At it’s heart, The Eagle tries to be a buddy film. It’s about the Roman Marcus learning that he should respect the Britons, and he does so by his alliance with the British Esca. Both men realize the value in honor in both cultures, and although they return the Eagle to Rome, they end up blowing everybody off to go…well, we don’t know what. My guess is hold hands. This message gets lost as neither Marcus or Esca is allowed too much conflict within themselves or with each other. The film is entertaining, but uses history as a fun backdrop to cause the drama of a specific man, rather than, you know, as history.

SOURCES:

Guy de la Bedoyere. Roman Britain. This book covers the conquest of Britain and the years following in the first part and spends the rest of the time covering cultural aspects of Roman rule, such as money, governing, slavery, and religion.

Peter Salway. The Oxford Illustrated History of Roman Britain. This takes a chronological approach to things, following the early Romans in Britain up through the fourth century.

FOR NEXT WEEK:

I’m going to tackle Gettysburg. This will likely take a lot of reading (the movie is based on a book which analyzes the battles). I will try to get this done in an efficient manner, but if I don’t then I might do a review of the first 3-4 episodes of The Tudors. Before talking about Gettysburg specifically, I would also like to do a cultural post that talks about the start of the Civil War and some of the battles leading up to this big one. Expect one of the following two schedules.

Plan A: Wednesday/Thursday – cultural post on Civil War, Saturday/Sunday – review of Gettysburg

Plan B: Wednesday/Thursday – review of some of The Tudors, following Wednesday – cultural post on Civil War, Saturday/Sunday – review of Gettysburg